Table of contents:

1. The concept of the sustainable town/city

2. From the Charter of Athens to the

Charter of Aalborg

3. From hygienism to the sustainable

town/city

4. New constraints: the urban microclimate,

energy infrastructures, recyling

5. Present experience/case studies

6. Difficulties in application of sustainable

urban development

7. Study in depth

1. The concept of the sustainable

town/city - introduction

“Why should we accept the

idea of an economy in full expansion as a way of salvation when

in reality what we need is a balanced economy which places the necessities

of life before profit, prestige or power” Lewis Mumford

European - and world - history of

the ideal city is a long one, a permanent quest by humanity for

a built environment most adapted to the needs of our civilisations.

Study

in depth: La cité idéale en occident à travers

l'histoire (The ideal occidental city through history) >>>

Today, the concept of the sustainable

town/city which a few years ago was attributed to the aspirations

of an environmentalist’s utopia is starting to stimulate the

urban debate.

The concept made one of its first appearances in

the UNESCO programme ‘Man and Biosphere’(1988). However,

it is primarily within the context of the Rio Summit (1992), that

this concept starts to attract attention. The European Campaign

for sustainable towns & cities initiated in the Danish town

of Aalborg (1994), polarises awareness in European towns & cities

by offering frameworks for meeting, reflection and exchange encouraging

the implementation of local strategies for sustainable development.

Sustainable development starts to be integrated

into policy-making, urban transport, and projects of urban planning.

Judicial and statutory frameworks are put in place but their impact

is limited. In the field, initiatives for sustainable development

often suffer from a lack of support, tools or efficient leverage.

Despite these limits an urban

vision is emerging that is not lacking in coherence.

A priority of the sustainable town/city is to instigate

a new dialogue between urban habitat and terrestrial habitat. A

local/global relationship is woven, differing to that fostered by

insertion into world economic competition.

Wind, waves and vegetation: the planet is not inanimate. It is a

living organism…every element of the planet’s biosphere

is a constantly renewed surface / Ref. "Cities for a small

planet" / Richard Rogers / 1997

Evidence from space of man’s physical impact on the planet’s

surface. We are now literally shaping the face of the planet. With

20 million residents, the metropolitan area of Tokyo forms the world’s

largest city / Ref. Science Photo Library.

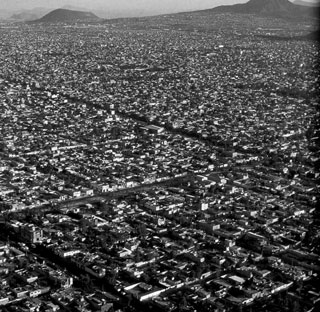

The Endless City: Mexico City’s population has grown from

100,000 to 20 million in less than a hundred years. People continue

to pour in from the countryside at the rate of 80,000 per month

/ Photo: Stuart Franklin

The steepest growth rate has been in cities. In the 1950’s

29% of the world’s population was urban. In 1965 it was 36%,

in 1990 50%, and by 2025 it could be at least 60%. / Ref. "Cities

for a small planet" / Richard Rogers / 1997

A second stake is the anchoring of the ecological

question to the social question, on the one hand because today the

environment is a question of society: political, urban, industrial

and agricultural choices, and on the other because social inequality

is often intensified by ecological inequalities. Granting that the

body of society is subjected to a number of risks, urban cartography

clearly shows parallels between zones exposed to high pollution

levels or more localised risks and territories that are socially

weakened.

A third stake is democratic: sustainable development

is a good support with which to open up public debate on the validity

of the present management of land – that of considering land

as a commodity. Land speculation often has more impact on urban

planning than projects established according to environmental imperatives

and the real needs of the population. A fundamental review of the

way land is managed seems indispensable in order to allocate real

power to local communities and local authorities to forward a more

ecological and equitable built environment.

The ambition and complexity of this programme invites

a certain amount of reserve when attempting to define a sustainable

environment because there are no clear-cut answers to the questions,

challenges and contradictions highlighted by sustainable development.

Furthermore, the diversity of local approaches is not easily definable.

Whilst the stakes for a sustainable town/city hold some common ground:

policies are contextual, adjusted to local cultures, local ecology

and territorial specificities. The notion of the sustainable town/city

is constructed within both a local and global context: between an

imperative of respecting local diversity and the necessity of adhering

to the vision of urban sustainability.

2. From the Charter of Athens to the Charter of Aalborg

The assertion of sustainable development

in the urban landscape engages with a broad questioning of modern

urban planning born in the wake of the Modern Movement in the 1930’s.

In parallel a sort of hygienism comes into play beneath the surface.

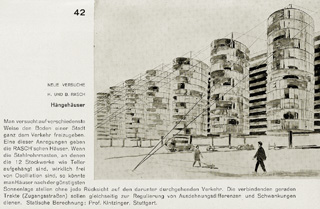

Ref.: "Befreites

Wohnen, 85 Bilder, erläutert von S.Giedion"

Study

in depth: La ville moderne / Les visions du C.I.A.M. 1930 / Existenzminimum,

hygiène et santé...

(The modern town/the visions of C.I.A.M. 1930 / Existenzminimum,

hygiene and health…) >>>

The dysfunctions induced by the model of the Charter

of Athens and its applications are at the heart of 'The Green Book

on the Urban Environment', which marks a turning point in 1990 in

the outlook towards the urban environment by the European Commission.

The European campaign for sustainable towns & cities in 1994

concludes with the drafting of the Charter of Aalborg.

Sixty years or so separate the elaboration of the

Charter of Aalborg with that of the Charter of Athens. This new

Charter advocates urban policies that integrate the impact of short

and long-term development on the environment and questions some

founding principles of the Charter of Athens.

Ref.: Revue "Urbanisme",

N° 330

The principle of the ‘clean sweep’

of the Charter of Athens is contested and instead the value placed

upon patrimony and heritage is enhanced. The patrimonial and cultural

dimension of the town/city is imposed as a central element of its

planning.

Ref.: La ville de trois millions d'habitants

/ Le Corbusier (1922) / Virgilio Vercelloni, "La cité

idéale en occident"

(Town of 3 million inhabitants / Le Corbusier

(1922) / Virgilio Vercelloni, “The ideal city in the Occident”)

The removal of modern architecture from context,

fed by industrial standardization and the modern international style,

gives way to concern over the adaptation to milieu and improvement

of local identities. This adaptation can take place through looking

to the past and an over indulgence of the neo-vernacular register

(dreaded by the Modernists) but can lend itself equally to a very

contemporary architecture capable of chiming with the site or landscape,

the patrimony, light or vegetation.

Borneo Sporenburg, Amsterdam, Netherlands

‘Zoning’, a key term in the Charter

of Athens is substituted by research into ‘mixed-use nodes’

with potential to enrich an urban landscape through integral use

of space, reducing journey requirements, through proximity of activities.

Compact mixed-use nodes reduce journey requirements

and create lively sustainable neighbourhoods / Ref. "Cities

for a small planet" / Richard Rogers / 1997

The paradigm of traffic flow and

fluidity implied by separating traffic according to modes of transport

opens up the debate about traffic in towns & cities.

Ref.: "L'urbanisme contemporain- Des

origines à la Charte d'Athènes"

(“Contemporary urban planning” Origins of the Charter

of Athens)

Ref.: "L'urbanisme contemporain- Des

origines à la Charte d'Athènes"

(“Contemporary urban planning” Origins of the Charter

of Athens)

Ref.: "Befreites

Wohnen, 85 Bilder, erläutert von S.Giedion"

The re-appropriation of the highway

by all modes of transport becomes a strategy to moderate automobile

traffic and regain public space.

Cars, cars, cars: By the middle of the twentieth centry, there were

2.6 billion people on earth and 50 million cars. In the last fifty

years the global population has doubled while the number of cars

has increased tenfold. In the next twenty-five years the world population

of cars is expected to reach a billion. Mass motorisation has arrived

and is set to spread to every city in this world / Ref. "Cities

for a small planet" / Richard Rogers / 1997

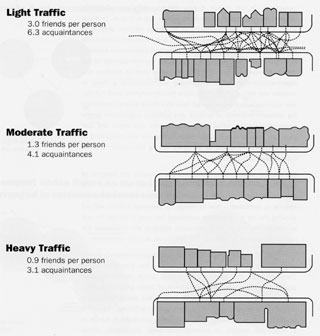

Friends or traffic ? A "Pedestrian

traffic flow Research" in San Francisco confirms the simply

reality that urban traffic undermines a street's sense of community.

In a single neighbourhood tree streets with different intensities

of traffic are compared. As traffic increases so casual visits to

neighbours decline. Traffic is a signific cause of urban alienation.

/ Ref. "Cities for a small planet" / Richard Rogers /

1997

Short cut,

go to chapter: La mobilité…( Mobility …)>>>

Instead of rationalist urban planning by experts, the Aalborg Charter

promotes a policy based on partnership and participation of the

town/city itself. New ways of working together are advocated, which

should involve a number of the population interested in the theme.

Sustainable development confronts the decision-makers with the complexity

of the decision; revealing to them what they are unable to control.

Passing through this phase of uncertainty and collaboration means

that one accepts that the answers that one held no longer function

in an optimum manner.

| The Charter of Athens 1933 |

The Charter of Aalborg 1934 |

| Principal of the ‘clean sweep’ |

Patrimonial attitude (heritage)

Improvement of what already exists

|

| Disregard of architecture in relation to surrounding

context (historic, geographic, cultural, ecological)

International style

|

Insertion of construction/building development

in a multi-dimensional environment

|

| Zoning |

Mixed-use function and cross disciplinary politics

|

| Facilitation of traffic flow

Separation of different modes of transport

|

Constraints to reduce traffic

Re-appropriation of public highways by all modes of transport

|

| Urban planning by experts

Geometricalisation and rationalisation of the town/city

|

Participatory urban planning

Singularity of solutions/answers

|

Contradicting points of view between the Charter

of Athens and Aalborg/ Cyria Emelianoff ‘La notion de la ville

durable dans le contexte europeen: quelques elements de cadrage”

(“The notion of the sustainable town/city in a European context:

some framing elements”) in ‘Enjeux et politiques de

l’environment’, cahier francais no.306, janvier-fevrier

2002

3. From Hygienism to the sustainable town/city

Comparative interplay can be observed

between the policies of hygiene and sustainable development. In

the case of hygiene, it is the excessive policy operating in its

name rather than its basic approach that may be called into question.

Numerous environmental problems are not visible or are not matters

directly relating to hygiene. Carbon dioxide is colourless and odourless,

pesticides are scarcely detectable, chemical products which can

interfere with hormonal systems were (yesterday) considered inoffensive.

At the other end of the scale, global warming, over-fishing, soil

erosion, biodiversity, desertification and deforestation have little

to do with hygiene.

Questions to do with environmentalist hygiene have

widely shifting emphases.

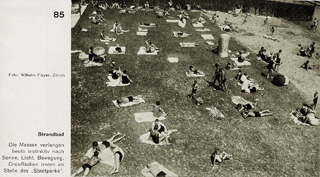

Ref.: "Befreites Wohnen, 85 Bilder, erläutert

von S.Giedion"

Study

in depth: La ville moderne / Les visions du C.I.A.M. 1930 / Existenzminimum,

hygiène et santé...

(The modern town/the visions of C.I.A.M. 1930 / Existenzminimum,

hygiene and health…) >>>

The race for cleanliness, and against pollution,

the opening of an office for complaints, square meters of green

space do not make up a policy of sustainable development.

In the urban landscape and in the Occidental context,

urban sustainable practices go as far as overturning the political

principles conducted in the X1X century. Necessary in their day,

as was the response of modern urban planning, they no longer correspond

to present imperatives.

Hygienists of the X1X century worked to increase

space within towns/cities creating wide avenues. They encouraged

‘zoning’ that is the separation of functions/activities

and populations.

Policies of sustainable urban development take

opposing action to this approach. The extension of city limits advocated

by the Moderns following the hygienist movement is replaced by the

opposite concern of containing urbanization, braking growing consumption

of space, infrastructures and energy. Traffic is no long a remedy

to the problems of hygiene but on the contrary is one of the main

factors of pollution in a town/city. Policies for urban spatial

planning have been so successful that ways of urban ‘tightening’

are necessary in order to control or even simply manage mobility.

The X1X century strove to make urban ground impermeable

and to cover canals - to dry out the towns/cities in order to curb

putrefaction transmitted by the ground and water. Water is being

found to have its attractions however, in today’s urban environment

for its recreational, ecological, aesthetic and refreshing qualities

There is a revival of the waterways networks in

towns/cities as rivers and canals covered over in the XX century

are restored to the open air, pathways along river/canal banks are

reopened, wetlands in and around urban areas are restored and abandoned

fluvial ports are refurbished.

The hygenic propensity towards expansion of green

space is equally replaced by more qualitative visions, concerned

with vegetation and landscape composition, continuity or ecological

corridors to favour biodiversity or different ways for use of nature

in an urban environment.

| Hygienist policies |

The policies of sustainable development |

Creating urban spaces (purification, deconta-

mination, improvement, airing)

|

Concentration/compacting to curb urban

sprawl

|

| Drying-out of towns/cities:

- covering up canals/waterways

- containment of rivers

- abandoning wetlands/marshes near urban areas

|

Rehabilitation of wetlands:

- project of reopening canals

- refurbishment of fluvial ports

- restoration of marshes near urban areas |

Making urban ground impermeable

Laying tarmacadam

|

Making urban ground permeable |

| Burying the water-cycle |

Management of rainwater

Lagooning

|

| Policy of expansion of green spaces |

Siting green spaces beside waterways

Policy of continuity of green spaces

|

A progressive departure from

hygienism / Cyria Emelianoff ‘La notion de la ville durable

dans le contexte europeen: quelques elements de cadrage” (“The

notion of the sustainable town/city in a European context: some

framing elements”) in ‘Enjeux et politiques de l’environment’,

cahier francais no.306, janvier-fevrier 2002

4. New Constraints: The urban microclimate,

energy infrastructures, recycling…

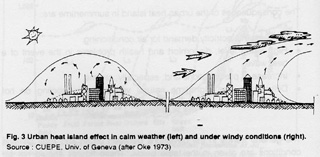

Last but not least

we are confronted by new phenomena such as problems of flooding

and the limits of the capacity of purification plants due to the

impermeable nature of urban ground and the heat island effect of

urban heat generated by the process of urbanization associating

heat sources and storing capacity too great in relation to efficiency

of natural mechanisms of cooling available. The transformation of

land also implies control of modification of natural energy cycles.

Photo: Kalke Village shopping complex green

roof, Vienna

Heat-Island effect

Short cut,

go to chapter: Microclimat urbain...(urban microclimate…)>>>

Recycling in all imaginable ways is equally desirable:

natural treatment and filtering of water, reuse, recycling or downcycling

of construction materials and all ‘consumable’ products

in general.

Water recycling management: Domestic water

is filtered and reused for irrigation / Ref. "Cities for a

small planet" / Richard Rogers / 1997

Linear metabolism cities consume and pollute

at a high rate / Ref. "Cities for a small planet" / Richard

Rogers / 1997

Circular metabolism cities minimise new inputs

and maximate recycling / Ref. "Cities for a small planet"

/ Richard Rogers / 1997

Revalorisation of the energy value of domestic

waste or the production of biogas from green waste allows for electricity

production or covers heating needs of buildings through long distance

heating networks.

The conventional system / remote power generation

/ Ref. "Cities for a small planet" / Richard Rogers /

1997

The compact model / local power generation

and waste recycling / City waste should

be seen as a resource to be mined. / Ref. "Cities for a small

planet" / Richard Rogers / 1997

Short

cut, go to chapter: Infrastructures de l'énergie... (Energy

infrastructures…)>>>

Solar access, already considered important by the

Modern Movement motivated by research into well-being and public

health, takes on significance today which is more closely associated

with questions of energy independence and atmospheric pollution.

Hence a search for urban structures, which exploit the advantages

of passive solar energy through carefully orientated glass facades

and the use of roofing for the installation of thermal or photovoltaic

solar collectors.

Photo: thermal solar collectors, ilôt

13, Geneva, Switzerland

Photo: Solstis, Etablissement Cantonal d’Assurances

(ECA), Lausanne

Short

cut, go to chapter: Infrastructures de l'énergie... (Energy

infrastructures…)>>>

Another challenge of the XX1 century is the integration

of windparks in the landscape...

Photo: Danemark

Photo: Windpark in Palm Springs (California)

Photo: Windpark in Tehachapi, USA

5. Present experience/case studies...

Today, existing trials for the sustainable town/city

are rather marginal but as they are increased, they demonstrate

a diversity that reveals quite different approaches from which the

concept can be addressed. In spite of contrasting appearances, which

may often reflect either regional or cultural particularities, these

trials can serve as examples for the whole of the European territory.

Eurotechnics, ecolabels

and ecobudgets

An initial approach targets ecotechnics and the ecological labelling

of products by businesses or even local authorities. This approach

lays out an ecosystemic conception of the town/city: multiplying

instruments of evaluation, elaborating an ecobudget, putting a system

of environmental management into place and aspiring to label products

for ‘good’ conduct in relation to water, air and different

pollutants. Ecological clauses are introduced into commercial contracts

and buying ‘green’ encourages businesses to adopt improvement/

‘reconversion’ strategies favourable to the environment.

Restrictions and taxation laws that favour ecology are main levers

towards the development of environmental techniques in industry

and, for example, marked advances in the sphere of ‘environmentally

friendly’ buildings. At the same time, ‘green’

consumerism will assert itself with the growth of labelled products

and environmental competition.

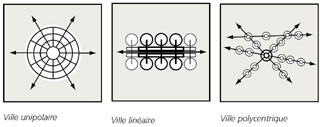

Planning the ‘compact’

town

This relates to the containment of urban and suburban expansion

through favouring density – compact mixed-use nodes with pedestrian

zones and restricted speed traffic zones, which improve the quality

of life in densely populated areas. Several planning axes can be

distinguished: planning public transport in conjunction with home

and workplace, organising public transport (railways) on a regional

and urban scale where urban concentration is in the vicinity of

public transport infrastructures and a compact organisation of the

town/city (linear, unipolar or polycentric), which aims to limit

travel. The installation of ‘green’ frameworks channel

urbanization whilst providing ecological and recreational resources.

Compact nodes linked by mass-transit systems

can be arranged in response to local constraints / Ref. "Cities

for a small planet" / Richard Rogers / 1997

Unipolar, linear and polycentric towns/cities

/ Ref.: "La Ville dense et durable. Un modele europeen pour

la ville ?" in "Vues sur la ville - Observatoire universitaire

de la ville et du développement durable" / Béatrice

Bochet, Jean-Bernard Gay , Giuseppe Pini / octobre 2002 and octobre

2003

On an infra-urban level the development of new

sustainable neighbourhoods, which have had some success in Germany

and other countries, can be observed. Built on disused docklands,

military or industrial wastelands they constitute both a ‘showcase’

and evidence of sustainable urban planning. They are most often

integrated into a sustainable development policy carried out on

the level of agglomeration. These planning processes are based on

the search for the ‘compact’ town - less energy consuming

and economical in space. The concept of the sustainable town/city

is often translated into ‘compact town/city’ or ‘a

town/city of short distances’.

Photo: Stadtteil Freiburg-Vauban, Germany

Photo: Quartier Kronsberg, Hannover, Germany

Photo: Borneo Sporenburg, Amsterdam, Netherlands,

a new prototype for low-rice high-density housing in Amsterdam's

docks

Social and Ecological

rehabilitation

Another approach is to grant social and ecological refurbishment

programmes to old buildings, small blocks or larger neighbourhoods.

The permanent reuse of places and of the urban fabric is an acceptance

of the sustainable town/city and its possibilities for self-renewal.

Photo: Rehabilitation of ‘ilot’

(‘block’)13, Geneva, Switzerland

The quality of the urban

landscape

This kind of project relies on the inclination of the urban landscape

and its qualities. The urban environment is perceived in its architectural

and aesthetic dimension and appreciated in association with the

quality of its open spaces. This approach puts an emphasis on sensitive

relationships, both social and cultural that are established between

the inhabitants and their town/city.

6. Difficulties in application of

sustainable urban development

The ease with which different strategies

may achieve a sustainable built environment and respect for the

environment as previously discussed is closely associated with management

of land. It is no accident that the great majority of sustainable

neighbourhood experiences are situated within contexts where public

authorities have an important say over a given territory. A broadening

of municipal power appears to be an essential condition for planning

and especially setting in motion the elements that constitute the

sustainable town/city without economic or speculative constraints.

Land, a commodity: the adverse effects

of mismanagement of land

At present totally reckless, irresponsible management of land allows

and imposes excessive speculation. The prices of the urban built

environment (flats, offices, commercial surfaces and other) increase

and the result of this is to reserve the latter for wealthy inhabitants

and businesses, creating social segregation and urban sprawl. The

town/city dweller no longer chooses his accommodation with a view

to practical criteria such as proximity between workplace and home

or between family and friends, but only in accordance with availability

of affordable accommodation.

Setting urban planning

in motion: difficult without true control of land by public authorities

It should be highlighted today, that in spite of the awareness that

a policy of high-density housing/building is indispensable, land

management practices, which consider land as a commodity jeopardise

the establishment of measures in favour of this objective. Only

strong policies tending towards at least partial state control over

land that is still available (agricultural land not permitted for

development) and policies enabling public authorities to acquire

land and buildings still available on the market, can guarantee

the setting in motion of building development that respects the

environment and is equitable for the population in the medium or

long term.

Ideas for a more reasonable

management of land: the example of Holland

Management of land such as practiced in Holland, for example, involves

the intervention of public authorities in relation to land ownership

(policies of acquisition, leaseholds etc.) favouring and greatly

simplifying the process of planning/management of land whilst remaining

compatible with a market economy engaged with commodities other

than land. These countries gain enormous advantages, and in the

long term, through being able to offer their citizens a well thought-out,

affordable built environment that is much more easily adaptable

to demographic, social and mobility needs, and last but not least

to environmental imperatives.

It is perhaps apt to remind those tempted to think

that this type of ‘collective’ land management is of

communist/marxist ideology, that many reputable economists (including

several Nobel prize-winners) speak very highly of the considerable

advantages to be had from a more collective management of land and

warn of the risks which are run by a world economy based more and

more on money generated by the speculative bubble (reminder: the

collapse of the property market in Japan, where property values

fell by 40%, plunging the country into a ten-year recession from

which it is emerging painfully today).

The creation of sustainable urban development

is hardly dissociable from a broadening of public powers and by

fundamental questioning of the policy of management of land, which

still views land as a commodity.

Peter Haefeli, architect, scientific

collaborator at CUEPE (Centre universitaire d’etude des problems

de l’energie) Geneva University

Study

in depth: Politique de gestion du territoire … (the policy

of land management…)>>>

7. Study in depth

CYRIA_EMELIANOFF_Ville_durable_dans_le_contexte_europeen.pdf

Aalborg_charter_english.pdf

Aalborg_charter_french.pdf

Aalborg_charter_german.pdf

Aalborg_charter_italian.pdf

New_Athen_charter_2003_english.pdf

New_Athen_charter_2003_french.pdf

BOCHET_GAY_PINI_La_Ville_dense_et_durable_Un_modele_europeen_pour_la_ville.pdf

VUES_Ville_durable_et_mobilite.pdf

http://www.unil.ch/igul

http://www.unil.ch/igul/page14548.html

NZZ_Holland_Triumph_der_kunstlichen_Natur.pdf

NZZ_Wir_gestalten_die_Niederlande_neu.pdf

EUROPE_Sustainable_local_energy_policy_in_european_towns.pdf

|

![]()